We Belong to One Another

A reflection on traveling by train, the necessity of fidelity, and the art (film, painting, and story) that I'm enjoying.

Dear friends,

Hello! I am writing to you from a train winding along the sparkling Pacific Ocean. One of the most quotidian joys, I think, is that of traveling by train- sipping a coffee, listening to an album, and watching the landscapes blur by. I commute to my master’s program on this train, and never fail to remain charmed by the fact that this trip isn’t just more sustainable than driving down twice a week- it makes you glad to be alive witnessing things like the California coastline on “the birth day of life and love and wings: and of the gay great happening illimitably earth” (e.e. cummings in one of his most beloved poems of mine, “i thank You God for this most amazing”).1

For worship this past weekend, I attended the Divine Liturgy at my local Byzantine Catholic Church and was particularly struck by this line in the bulletin: "as members of God's family, we belong to one another, and so we live in an active community life as Church. Most importantly, we join one another to worship in Christ.”

I’ve recently been reflecting a lot about the extent to which day-to-day life in this day and age has become largely oriented around the self. From self-help Instagram pages to The New York Times’ Well vertical, we are encouraged more than ever to put ourselves first.2 While, of course, there are situations where it is wisest to end a friendship, or to set boundaries, I worry much of it has evolved from tools for genuine betterment into a framework stressing personal benefits while dismissing moral responsibilities and communal values. I don’t believe that we are our truest selves as standalone people, but rather when in community, in the context of our relationships with one another and the non-abstract realities of forgiveness, resilience, and self-sacrifice- values that won’t always provide strong emotional comfort or personal gain.

For instance, my master’s degree isn’t an individual pursuit taking place in the confines of my mind, but rather something that has been brought about through ongoing conversations shared with incredibly wise and interesting people, both the ones directly in my life and those whose books and writing I’ve engaged with. Knowledge, truly, is relational; I was reminded of this in my first year of undergrad when I told my advisor I was having a hard time writing poetry and he told me that when my soul locates beauty, I have a responsibility to both multiply it and share it.

This all brings to mind the 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany’s with Audrey Hepburn. In the final scene, Holly Golightly’s love interest, Paul, tells her that he is in love with her. Cool and distant, she responds, “people don’t belong to people… I’m not gonna let anyone put me in a cage.” To which Paul counters: “people do fall in love. People do belong to each other, because that’s the only chance anybody’s got for real happiness.”

Holly’s plight, her insistence on remaining detached and refusing to belong to anything or anyone outside of herself, is something that’s so common it’s almost become ordinary. I’ve come across articles defending ghosting as an acceptable way in which to communicate with someone else, and other articles suggesting that we have been overemphasizing the necessity of forgiveness. “Lately, on social media, ghosting has been demonized and highlighted as an awful experience,” says the author of the first article, going on to suggest that seeking reconciliation in our relationships is falling prey to a “victim mentality” and we must attempt to focus on ourselves more.3

Wendell Berry has a lot to say on this, on how contemporary society must rework itself through detachment and reorient faithfulness in our center, writing, “Fidelity… give[s] us the highest joy we can know: that of union, communion, atonement.”4

Faithfulness, whether it be to a friend, a partner, or to one’s faith, is often faithfulness to a time when we had faith, as wrote the great Jewish theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel. It is a rare, special thing to be a person whose actions are evident of the reflection this requires, a person who understands that their actions and inactions carry moral weight, and that we are all a part of a tapestry made up of others- people we haven’t met and people we have the privilege of knowing deeply, because, “as members of God’s family, we belong to one another.”

What a gift it is to encounter the profound landscapes present inside one another and allow the “fat, relentless ego” (as Iris Murdoch would refer to it) to be transformed by the reality of our belonging.

Wisdom and Whimsy: Art I’m Enjoying

The Brambly Hedge series

Throughout the past several weeks, I have been finding tremendous delight in revisiting Jill Barklem’s Brambly Hedge series. As with the inviting, whimsical worlds crafted by Beatrix Potter and Brian Jacques (Redwall Abbey), Barklem’s Brambly Hedge has been a series of books that I have loved for quite some time. I must have come across something that reminded me of her illustrations (I think it may have been a Brambly Hedge-inspired recipe for mulled wine), and have now embarked on the quest to procure the complete collection from one of my local used bookstores.

These little books offer a glimpse into the lives of the Brambly Hedge inhabitants throughout the course of the four seasons of the English countryside, portraying the ordinary magic of this cozy and warm-hearted world. In the summer stories, the mice host a wedding on a bark and nettle raft, floating past buttercups and enjoying a midsummer feast of honey creams, syllabubs, and fresh salad from the kitchen of Crabapple Cottage. It’s good fun, and I’ll update you all if I successfully locate a copy.

Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups

My mom and I are watching through Terrence Malick’s films, and last week we sat down with Knight of Cups. The 2015 film sits squarely within Malick’s well-known stream-of-consciousness filmmaking style, following screenwriter Rick (Christian Bale) through an odyssey set in the background of Los Angeles and Las Vegas. It is divided into eight chapters, seven of these titled after a tarot card from the Major Arcana and each vaguely centered around a relationship with someone in his life.

Memory is a tremendous theme in Malick’s work, and it runs through the course of Knight of Cups, offering both a religious quest and a self-portrait of Malick. Rick is always on the outside of the inside of every scene in which he is depicted, and Malick’s separation of visuals from sound crafts a sort of propulsive coherence to this achingly self-aware narrative in which Malick positions himself as an industry insider, contrary to his general reception as a creative enigma known for his reclusiveness.

I read a really beautifully written review of the film by Richard Brody in The New Yorker, which concludes with: “But be honest about your experiences, about your failings—and about your enduring intimations of beauty even in places and situations that you’d hesitate to call beautiful, because the production of beauty in a world of suffering, and from your own suffering, is the closest thing to a higher calling that an artist has, the closest thing to the religious experience that art has to offer.”5

Andrei Bodko’s Always Near Series

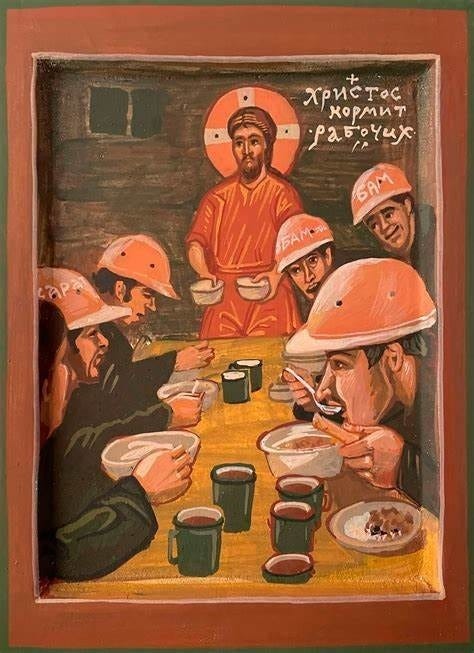

I have also found myself completely transfixed by Andrei Bodko’s series of paintings depicting Christ in the rhythms of contemporary life. Bodko’s Always Near is in the artistic style of pre-revolutionary “lubki”, the term for Russian woodcut prints often depicting scenes from folklore and spiritual themes. While he is a professional iconographer, he denies that his series is a series of icons, observing instead: “These are not icons, but religious paintings on Christian themes. How do we believe in Christ in the 21st century? Is he around, helping us? We believe that God is omnipresent, he hears every beat of our heart, sees all our thoughts. God is always near, but we don't see him. Sometimes, he helps and sometimes he just sympathizes.”6

I think that these icons of Bodko accomplish exactly what the “He Gets Us” evangelical campaign from last year’s Superbowl missed the mark on. While at first glance it appears that both have a similar objective- reinforcing the image of Christ that is in the here and now, walking alongside of us- the “He Gets Us” campaign received wide criticism due to its attempt to reframe Jesus as a sort of influencer, ending one particular ad with the slogan “Jesus was canceled.”7 But Jesus isn’t highly visible so much as always near- even when this means “unseen” in our contemporary eyes- and Bodko’s everyday depictions of Christ are able to thoughtfully convey this.

My Year with God by Svend Brinkmann

I found this little volume by the agnostic Danish psychology professor Svend Brinkmann at a bookstore last month and just started on it last week. My Year with God describes the year that Brinkman spent exploring the idea of what God and faith can bring to a modern world, wondering if the religious life can have significance for those that aren’t convinced that there exist profound spiritual dimensions to this life.

Each chapter centers around a particular question Brinkmann is asking, from “is there a link between ethics and faith?” to “does the soul exist?” I am very interested in this entire premise, and am reminded of one of the questions Christian Wiman poses in He Held Radical Light: The Art of Faith, the Faith of Art: what is the importance of poetry for those that don’t read it? Both thinkers appear to be asking the same question here.

Well, friends, I am signing off to enjoy a cup of coffee and to open the latest issue of Dappled Things. Please pardon my current inconsistency with these weekly missives, as I am in the process of determining my schedule for both work and my M.T.S., and am consequently in a bit of a liminal space trying to make sense of when will be best for nestling myself away and writing. Wishing you a gentle, joyous rest of your week!

Warmly,

Julia

Victoria Emily Jones, "‘i thank You God for most this amazing’ by e.e. cummings," Art and Theology, April 27, 2016, https://artandtheology.org/2016/04/27/i-thank-you-god-for-most-this-amazing-by-e-e-cummings/.

Can you say “yikes?”: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/27/well/mind/forgiveness-healing-peace.html. Freddie deBoer provides an excellent response to this article on his piece on therapy culture: https://freddiedeboer.substack.com/p/selfishness-and-therapy-culture?utm_source=publication-search.

https://www.elephantjournal.com/2022/09/why-ghosting-is-ok-and-learning-to-let-go-important/

Wendell Berry, Fidelity: Five Stories (New York: Pantheon, 1993).

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/terrence-malicks-knight-of-cups-challenges-hollywood-to-do-better

https://www.rbth.com/arts/337667-unusual-christ-paintings-russia

https://hegetsus.com/en/articles/did-jesus-face-criticism

I appreciate your writing. You’ve given me much to ponder.

Watching Terrence Malick’s films with you has been so enriching and I look forward to our next one.

I love how you incorporated that scene from Breakfast at Tiffany’s as well as Wendell Berry, helping connect us to your theme of community, connection, and the unique opportunity we have as humans to truly flourish when together and remembering we are ALL part of this ‘beautiful tapestry’ of life. Each piece comes together to make the Whole.

Andrei Bodko’s series he created are such beautiful depictions of Christ’s nearness and love. I recommend that everyone take a look at his work.

AND, I will definitely keep an eye out for used copies of Brambly Hedge. The illustrations are the sweetest, most wholesome and I just want to be in a little cottage in the English countryside with the critters. 💕