Week 6: Learning How to Die

This is the most hopeful story that we can tell about the world around us: remember death.

Hello friends!

I am writing to you all in the midst of yet another incredibly warm Southern California day, having just finished, à la Lorelai Gilmore, my third cup of coffee. I would like to defend the necessity of this decision, as it made it possible for me to catch up on the majority of my emails this morning and to organize three separate inboxes (everyone please cheer! You all must understand how significant this is!)

As for the reading for this week, it is hard to believe that we are wrapping up the final chapters of Pilgrim at Tinker Creek! In Chapter Eleven, Dillard writes about the swiftly arriving month of July and extensively discusses the German physicist Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976) and his Principle of Indeterminacy. She writes about how quantum mechanics, and specifically this principle, is so similar to mysticism, and observes that the physical world is ever-changing and always somewhat unknowable. In the next chapter, she goes on to talk about theodicy, emphasizing the importance of being fully present when in the natural world.

Chapters Eleven and Twelve: Thoughts

It appears to me that anyone who puts a lot of thought into living a good life tends to end up thinking about death. I, for one, certainly have. As a little girl, I remember (in the fashion typical of a four-year old) asking my parents countless questions about life spans and old age.1 I also remember when I was a little older and visited a cemetery for the first time with my Girl Scout troop; at the very end of the trip, we stopped at the grave of a little boy who had died when he was about my age. I felt tears burning at the corners of my eyes, and that was the first time I recall feeling deeply aware of the inevitably of death. For weeks after that, I remember waking up every morning thinking to myself, “this could be my last day here.”

I didn’t know it at the time, but I was echoing a sentiment expressed in Fr. Neil McNicholas’ A Question of Death & Life: A Catholic Approach to Dying:

“What it means is that the more comfortable we become with the reality of death, and the less we deny it, the more positively attuned we’ll be to the day-to-day things that remind us of our mortality.”2

A more recent experience with the idea of death occurred when I first entered the realm of “book Twitter” two or three years ago. I spent quite a bit of time tweeting about whimsy, books, and beauty, and consequently, the algorithm acquainted me with people who are also transfixed by Anne of Green Gables and try hard to describe the elusive joy found in sunlight and peonies. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the community that I have found in that subsection of Twitter, and why those friendships were so rich, engaging, and profound in spite of the fact that they were formed- and sometimes solely kept- online.

I think that part of the reason I get along so well with many of the individuals in book Twitter was this: we share similar perspectives on what it meant to live well and, consequently, to die well. We are transfixed by stories of all kinds, and because of this, we daily told ourselves a hopeful story about the world around us and the lives we lead. Happiness and grief are both streams that flow from the same body of water- a body of water underpinned by the conviction, felt deep in one’s bones, that life is meaningful, worthwhile. It demands that we pay attention to it, a sentiment which is noted plainly by Dillard when she observes the necessity of being “rapt and enwrapped in the rising and falling real world.”3 Of course, from the beginning of time, being entrapped in the world means being entrapped by death- there is no way around this, try as we might.

The real question is this: does being rapt by the world also mean being rapt by death?

At the beginning of a song that I love, “Learning How to Die” by Jon Foreman, he offers the listener these poignant words as an exchange between friends:

“And I said, please

Don't talk about the end

Don't talk about how

Every living thing goes away

She said; friendAll along I thought

I was learning how to take

How to bend, not how to break

How to live, not how to cry

But really

I've been learning how to die

Been learning how to die”

When I first listened to this song many years ago, the title startled me. What does he mean, “learning how to die?” Isn’t this in direct opposition of everything that matters to me, everything that I believe is worth paying attention to in the world?

There are an endless amount of voices in contemporary society telling us how to live a good life, whatever that may mean to each individual. There are the self-help books at Barnes and Noble, there are promises of endless youthfulness by YouTube makeup aficionados, there is the highlight reel of your daily life to post on social media. There is also the church, and despite the fact that evangelicalism is seemingly so fixated on death due to the passion narrative, I’ve noticed that most sermons about death are really just about the afterlife, just as most announcements of a member’s death in the church conclude with the reassurance that they’re now eternally healthy and joyful because they are with Jesus.

This discomfort that the modern, secular world seems to experience when facing our own mortality, such as when I first heard “Learning How to Die”, hasn’t always been the case. “Morality plays” is a term used by medieval scholars to describe the genre of dramas that were popular between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. Their official titles aren’t "morality plays”, but it is the most effective way for scholars to categorize and analyze these manuscripts. Morality plays were typically comprised of an average man who represented the whole of humankind, with supporting characters as metaphors for abstract concepts. These narratives are made up of three overarching moments: when Death first visits, the psychomachia, and Death’s capture of the protagonist (akin to the narrative visually depicted in the 1957 Ingmar Bergman film The Seventh Seal).4

In one of the most notable morality plays, Everyman, the Everyman prepares for Death by acquainting himself with the Virtues, such as Good Deeds and Beauty. Good Deeds is the only virtue to accompany him to Death (when crafting their own morality plays, Protestants in later centuries were displeased by this and went so far as to deem some of the Vices “Catholics”) and as Death captures the Everyman, he whispers, “Into thy hands, Lord, my soul I commend; Receive it, Lord, that it be not lost.”5

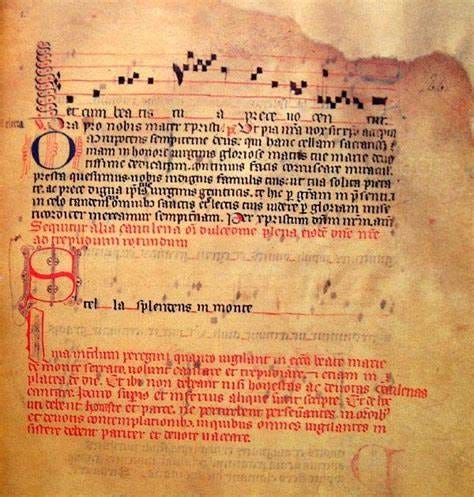

This idea of becoming comfortable with the idea of death, both emotionally and spiritually, is also common in early European music. Many of these songs are very much in the tradition of memento mori, as illustrated in the Llibre Vermell de Montserrat, a 1399 manuscript containing a collection of different medieval songs. A particular stanza in the English translation of one of these songs reads:

“Life is short, and shortly it will end;

Death comes quickly and respects no one,

Death destroys everything and takes pity on no one.

To death we are hastening, let us refrain from sinning.”6

As we have become more and more distant from death throughout the past several centuries, it seems that we have lost the ability to speak about death this plainly in the conversations that we have. Embracing death publicly is associated with being goth, and attempting to talk about death with family and friends can often leads to shocked expressions and perceived morbidity. In The Seventh Seal, the protagonist is determined to evade the character Death, telling himself that this will ensure that he can more deeply enjoy the time he has left.

Unfortunately, many of us behave in a similar way, telling ourselves that the less we think about death, the more we can suck the marrow out of life.

However, it is necessary for individual and communal flourishing to realize that part of telling ourselves a hopeful story about the world is talking openly about death, as well as learning to accept the reality of our own mortality.

What does this mean on a practical level? Well, organizations like Death Over Dinner and The Order of the Good Death are actively providing us with places to start.7 Death Over Dinner’s mission is to encourage having these difficult conversations about mortality through hosting a shared meal with one’s family and friends. Meanwhile, The Order of the Good Death was founded in 2011 by Caitlin Doughty with this goal:

“…committing to staring down your death fears—whether it be your own death, the death of those you love, the pain of dying, the afterlife (or lack thereof), grief, corpses, bodily decomposition, or all of the above. Accepting that death itself is natural, but the death anxiety and terror of modern culture are not.”8

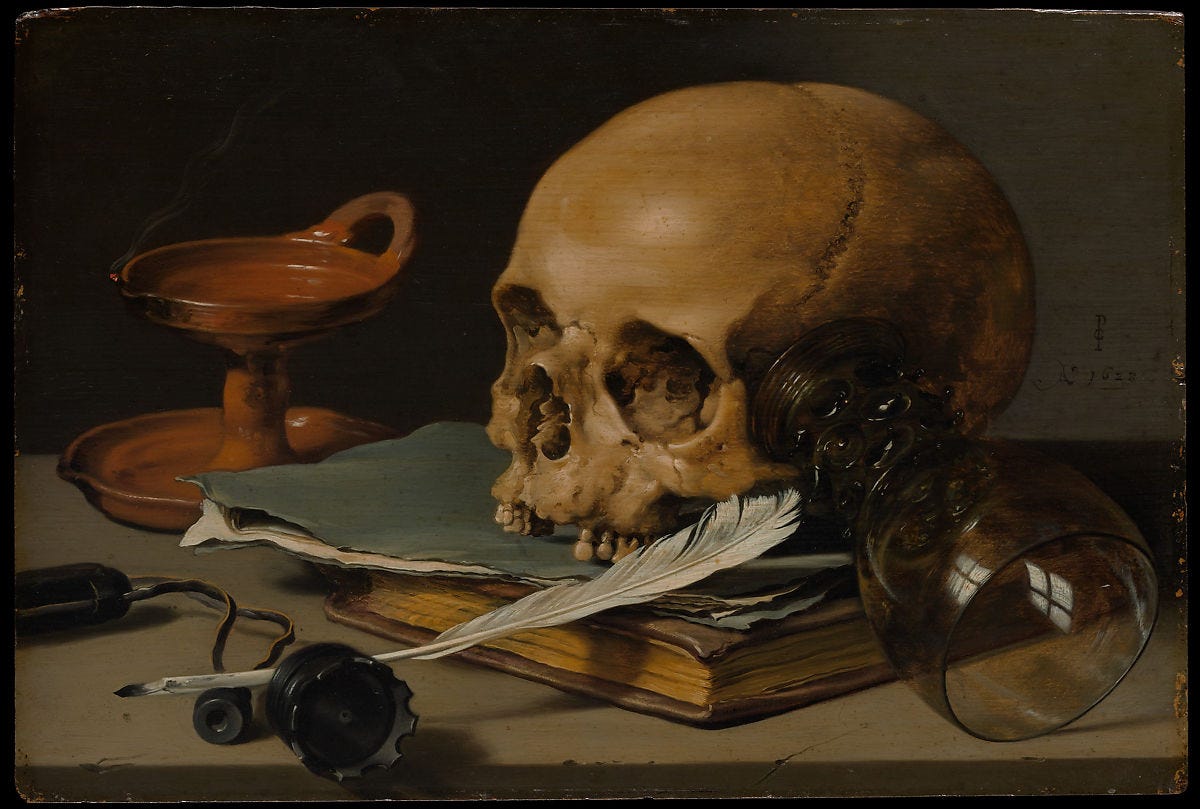

I think that a significant part of learning how to die is also learning to recognize and label death in all of its forms: the death of an opportunity, the death of a friendship, the death of spring, the death of the person you used to be. When we are more comfortable talking about death and actively identifying how death occurs in our daily lives, we are more prepared to encounter the responses that can be prompted by physical death, such as emotional trauma, strong anxiety, and profound and sustained grief. We don’t necessarily need to keep a human skull on our bedside tables, like the Italian saint Charles Borromeo was said to have done, but it is important that we begin to forge a more comfortable connection with both death and what it entails.

Much of this discussion brings to mind how the Catholic theologian Elizabeth A. Johnson wrote extensively about the practice of “native remembrance” in her work. In a chapter found in Systematic Theology: Roman Catholic Perspectives, Volume II, she talks about how we can remember saints that are not included in our formal liturgical practices, such as celebratory feast days, wondering how they can shape us even with very little physical, tangible remembrance. Johnson notes that “proclaiming the livingness of the dead in God alerts tyrants to their impotence: They do not have the last word.”9 An important response to death in the Christian faith is exactly this: continuing the work of the dead in the modern day by seeking justice for the living, working to bring heaven to Earth. Remembering the dead is not passive and fleeting; it is sturdy and important work, distinguishing memory as something that holds us together in love, even when we are no longer around to see our own work through.

Dillard is very wise when it comes to struggling with our own mortality. In her eyes, learning how to die is a practice that we must first observe in the natural world. She watches the green, flourishing leaves as winter wraps its icy blanket around every inch of them, and she wonders about the complicated, complex truths that are repeatedly coming into play within Tinker Creek.

“And what if those grasshoppers had been locusts descending, I thought, and what if I stood awake in a swarm? I cannot ask for more than to be so wholly acted upon… a little blood from the wrists and throat is the price I would willingly pay for that pressure of clacking weights on my shoulders, for the scent of deserts, groundfire in my ears…”10

Learning how to die is necessary, soul-staining work. It equips us with courage and compassion, drawing us closer in relationship with our family and friends and offering us the opportunity to remember the dead through the work of the living. It helps us to identify the everyday instances of death in our lives. Death inevitably carries with it so much pain, tragedy, and grief, and that isn’t something we should try to escape. Accepting our own mortality is necessary because it better equips us to handle all of the emotions that death can bring.

This is the most hopeful story that we can tell about the world around us: remember death. Memento mori. We are all going to die.

We are all going to die, but that was never the truest thing about the world and never will be. New trees will spring up in all of their glory, the living will continue the work that the dead cannot finish, and beauty will always fight for another say. And when we talk about the end, and how every living thing goes away, we are remembering how precious the world is. How it is worth paying attention to. How very serious it is, as Mary Oliver would say, “just to be alive on this fresh morning in the broken world.”11

Oh, and how we must start paying even a little more attention.

We are remembering the depths of hope and love holding this Earth together, and we are learning how to live; we are grieving the loss and absence that comes with every beloved thing we could ever have, and we are learning how to die. This is our most sacred work.

Here are some questions to consider for this week’s reading:

Is it important to spend a lot of time thinking about death? When, if at all, does thinking about death become “morbid?”

How would you describe the perspective on death depicted in medieval morality plays, the song from the Llibre Vermell de Montserrat, and The Seventh Seal?

What does “learning how to die” mean to you? Do you think that initiatives like Death Over Dinner are worth participating in?

Be well this week, friends. I am thinking of all of you and am so excited for the (final!) two weeks of our summer book club.

Warmly,

Julia

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/16/parenting/kids-talking-about-death.html

Fr. Neil McNicholas, A Question of Death & Life: A Catholic Approach to Dying (London: Catholic Truth Society, 2017).

Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (New York: McGraw-Hill College, 2000).

Ingmar Bergman, Randolph Goodman, and Leif Sjöberg, “‘Wood Painting’: A Morality Play,” The Tulane Drama Review 6, no. 2 (1961): 140–52, https://doi.org/10.2307/1124836.

Everyman, first published in 1485, reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, 2004.

https://www.artandpopularculture.com/Memento_mori

https://deathoverdinner.org/

https://www.orderofthegooddeath.com/

Elizabeth A. Johnson, “Saints and Mary,” in Systematic Theology: Roman Catholic Perspectives, vol. II, ed. Francis Schüssler Fiorenza (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1991), 168.

Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek.

Mary Oliver, “Invitation,” A Thousand Mornings (New York: Penguin Books, 2013).

I don't give much thought about my own mortality but I did find this to be extremely insightful. Thanks so much for the post.

"dying is easy, comedy is hard". Jack Lemon

Thoroughly enjoyed this week’s post. As you know, death and dying are one of my favorite topics to discuss. Another post that gives me much to reflect on. Thank you 😊