Theology Done on One's Knees

Reflections on the church and academy after the 2024 SBL/AAR annual meeting, as well as art that I enjoyed last month.

Dear friends,

I am writing to you (at last!) from one of my favorite little coffee shops in downtown San Diego. Several weeks ago, I spent the weekend attending the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature/American Academy of Religion, held at the San Diego Convention Center. Last year, I presented a paper on the Magnificat as part of a whirlwind trip to San Antonio during which I arrived at 11:30 PM, presented my paper at 9 AM the next day, and, at 2:30 PM, flew out to California for Thanksgiving. This year, I attended several days of the conference with a friend from my master’s program, and we were able to sit in on an incredibly diverse array of panels.

I may have several years of familiarity with the equally weird and wonderful world of academic theology under my belt, but I still find myself navigating the tension that I’ve perceived to be inherent to the field since I was first introduced to it. The careerism, self-promotion, and detachment of the secular academy seems to exist uncomfortably alongside discussions of God and beauty, the Kingdom and meaning.

In the days immediately following the conference, I find myself asking a question similar to that posed by Christian Wiman throughout the course of his wonderful little book He Held Radical Light: The Art of Faith, the Faith of Art:1

What is the importance of poetry for those who don’t read it? How does poetry transform the lives of people for whom it is seemingly irrelevant?

Or, more accurately in this case:

What is the importance of theology for those who don’t study it? How does theology transform the lives of people for whom it is seemingly irrelevant?

Years ago, my alma mater fired a professor of political science for claiming that Christians and Muslims both worship the same God. In December 2015, Dr. Larycia Hawkins made a Facebook post discussing her decision to wear a hijab during Advent as a profession of “embodied solidarity” with Muslims, stating that Christians and Muslims worship the same God.2 Media coverage was enormous, as this is very likely the most significant controversy the school has had. Wheaton anthropology professor Brian Howell wrote that this had become “…. a Rorschach test for those wondering about the state of Wheaton College, evangelicalism, and even U.S. Christianity.”3

At religious schools like Wheaton, faculty, staff, and students are required to sign their agreement with the school’s tenets of theological belief as the basis for their employment or enrollment in the institution. In citing Pope Francis’s claim that we all worship the same God, a sentiment that felt particularly poignant and necessary amidst the political landscape of 2015 America, and posting photos of her donning a purple hijab in the spirit of “embodied solidarity”, it was recommended to the president that Hawkins be fired. Administration said that she had failed “to accept and model the Statement of Faith of the College and/or the Community Covenant.” (Essential to acknowledge here is that she didn’t contradict any of the Statement’s explicit claims.)4

In the aftermath of her dismissal, a cartoonist for some paper or other drew an illustration depicting Hawkins and Jesus in conversation. The text shows Jesus telling her,

“Don’t worry, Larycia, I wouldn’t have been able to sign their statement of faith either.”5

I think about this a lot- about the fact that the second we write our theology, we need to be wary that it will begin to operate as a door rather than as a window. Theology can begin with the explicit and the systematic, but it cannot be confined there, which is why I read Wendell Berry, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Flannery O’Connor and am reminded, over again and again, that the best way to do theology is very often through a novel.

Prior to the scholastic era, in the days of the early Christians, “those who engaged in talk about God were assumed to have a relationship with God.” With the scholastic era, theology became academic in a way that it wasn’t before, by which I mean that commitment to one’s own spiritual life was no longer a precursor for involvement in the field. Within this framework, it isn’t hard to begin to see one’s theological contributions as works of personal genius rather than as the natural extension of both love for God and the desire to participate in the salvific work of the Kingdom. (With this, I think of how many modern Christians frequently point to C.S. Lewis as an example of a favorite theologian, neglecting to remember that Lewis did not consider himself a theologian.6 His vocation as a Christian was the same as his vocation as an artist, and because the expectations for lay involvement in theology are so low, we deem him a theologian and manage to forget that the depth of his understanding of and interest in Christian theology is very sincerely what all laypeople are called to.)

Hans Urs von Balthasar, who was a Swiss theologian and priest but also, and perhaps most profoundly, a poet, said that theology proper can only be done on one’s knees.

He wrote about the distinction between what he deemed the “sitting” and “kneeling” theologies, and Pope Benedict XVI expressed a similar sentiment to this, saying:

“Theology is based upon a new beginning in thought which is not the product of our own reflection but has its origin in the encounter with a Word which always precedes us. We call the act of accepting this new beginning ‘conversion.’ Because there is no theology without faith, there can be no theology without conversion.”7

Poetry is about bringing eternity into one’s immediate consciousness, and I think that this should be true of the very foundation for our doing theology also. In studying God and beauty, goodness and the sacraments, we are provided with the imagination to see what is sacred in everything. “I wish I had paid more attention,” is often what we think after emerging from a beautiful moment, where the world seems in complete excess of itself. And then: “If I could do it over again, I would have paid more attention.”

The study of God and the worship of God cannot be detached, and this is why our great call is to extend our attention forth as prayer. It is in this way that theology, just as with poetry, carries relevance for those who don’t study it- those who may never sit in a classroom or read a magisterial document. Theology must be done on one’s knees.

Wisdom and Whimsy: Art I’m Enjoying

The film Babette’s Feast

I watched this film for the first time years ago. This Danish drama from the 1980’s tells the story of two pious Protestant sisters who oversee the small congregation of their late father, a pastor. One day, Babette Hersant, a refugee from Paris, arrives on their doorstep and becomes their cook for the next fourteen years. At some point, she ends up winning the lottery and decides to move away from the little village, and to show her appreciation for all of the people that she has grown to know and love, she prepares a deeply exquisite meal, a “real French dinner.” At the end of the film, it is revealed that she spent all of her money on the meal, and she will not be returning to France, as expected by the sisters. One of the sisters wrings her hands, saying “now you will be poor the rest of your life!” and Babette responds, “an artist is never poor.”

It’s a deeply beautiful film- a feast for the senses and the soul. Babette’s Feast is brimming with religious themes (hospitality, self-sacrifice, incarnational faith), the most apparent of which is the way that Babette’s relationship to the puritanical community serves as allegorical to Christ’s actions on behalf of the church, with her elaborate feast as the Eucharist. What stands out most for me, perhaps, is an idea best articulated in Gaudium et Spes: the idea that man cannot truly find himself “except through a sincere gift of himself.”8 It speaks to the idea that our desires don’t need to be adjudicated so much as renewed, and the film is very much worth a watch.

The Awakening of Miss Prim by Natalia Sanmartin Fenollera

I’ve reread this charming little novel every December for the past six or seven years. It was first published in Spanish in 2011 and was then translated into English several years later. The Awakening of Miss Prim tells the story of a young woman who comes to the village of San Ireneo de Arnois for the position of private librarian for a gentleman and his children. She quickly realizes that this little community she finds herself in is staunchly, idiosyncratically distinct from the rhythms of the modern world. Her days are filled with lively conversations about everything from Jane Austen to the various waves of feminism to icons, and by the end of the book, the reader is made aware that Miss Prim’s time in San Ireneo is not a pilgrimage, but a conversion.

“Conversion,” Evelyn Waugh writes in Brideshead Revisited, “is like stepping across the chimney piece out of a Looking-Glass world, where everything is an absurd caricature, into the real world God made; and then begins the delicious process of exploring it limitlessly.”9 I particularly like this segment from a 2021 interview with Fenollera, and written up by José María Sánchez Galera for a Spanish newspaper:10

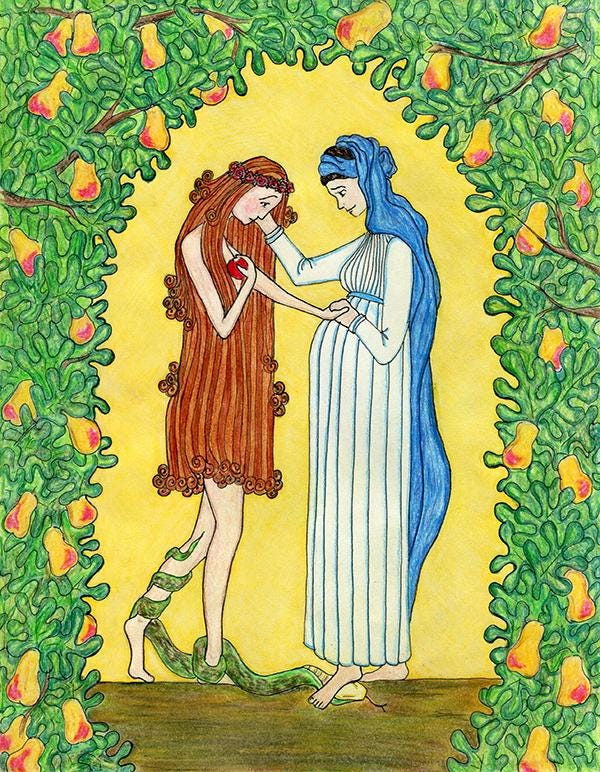

“Mary and Eve” by Sr. Grace Remington

This image of Mary and Eve is a pencil and crayon drawing by Sr. Grace Remington, one of the Cistercian Sisters of the Mississippi Abbey in Iowa (they have been supporting themselves selling all sorts of lovely chocolates and caramels for over fifty years!). In this image, Eve is depicted as looking down in simultaneous sorrow and shame, clutching the apple as the snake crawls down from her leg, its head crushed beneath Mary’s foot. Mary is shown with a face of warmth and compassion, holding Eve’s head with her hand while Eve’s hand is placed against Mary’s pregnant stomach.

What consistently stands out to me in this image is the way in which the entire drama of Creation, the Fall, and the Redemption is told between two women. Mary isn’t looking at the snake, because the weight of her attention is completely focused on Eve. She is crushing the snake while also crushing the isolation and alienation that so often accompany our experiences of sin. It reminds me of how so much of Advent- a time of yearning, annunciation, preparation, and joy- is centered around communal hope, the collective posturing of ourselves towards the promise of Incarnation.

Sr. Grace has noted, in an interview with Plough magazine about this piece of hers:

“One of the things I was pondering as I drew this picture was the question of why Eve said ‘no’ to God and Mary said ‘yes’… I wondered whether Mary was able to give her yes precisely because she knew the pain of life. She knew how desperately we needed God. Her eyes were open. This was part of what I see as her compassion for Eve in this picture. She is not standing with folded hands on a pedestal above Eve: she is standing with Eve, touching Eve, seeing her deeply. She knows the gift she is carrying is for Eve as much as it is for herself. She doesn’t need Eve to get herself together, or to even drop the apple before inviting her in.”11

“Annunciation” by Denise Levertov

It is no secret that the Church has a long history of sanitizing the roles of women throughout church history. We are taught about the simplicity and sweetness of St. Thérèse of Lisieux (“The Little Flower”), but never the fierce calling and longing articulated in her diary, where she writes: "I feel the vocation of a Priest! With what love, my Jesus, would I bear You in my hands, when my words brought You down from Heaven!” And with the Blessed Mother, we cherish her obedience and servanthood while often overlooking both her willing consent and emboldening display of courage.

Levertov’s poem helps expand our imagination as it relates to both Mary and the Incarnation, reminding us that the gentleness and obedience so often affiliated with our image of her are not cause for concern until they’re used in an exclusionary way.12 I’m currently writing a book chapter on this very topic- the evolution of artistic depictions of Mary beginning in roughly the first century. Imagery that denotes the mother of Christ as merely meek and lowly overlooks the powerful prose of the Magnificat that is centered around the struggle for justice and the path towards collective liberation as is reminiscent of inaugurated eschatology.

Okay, now I must sign off to go 1) enjoy a warmed blueberry scone and perfect cup of tea and 2) work on a paper on St. Bonaventure, Piranesi, and re-enchantment. Wishing you all a gentle weekend, and a completely wonderful Second Sunday of Advent.

Warmly,

Julia

Christian Wiman, He Held Radical Light: The Art of Faith, the Faith of Art (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018).

Hawkins’ words remain poignant and necessary (required reading, I’d say) for all Christians; in my view, the controversy that ensued at Wheaton is proof of this. You can read her post here: https://www.facebook.com/larycia/posts/10153331120918481.

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/16/magazine/the-professor-wore-a-hijab-in-solidarity-then-lost-her-job.html

https://www.wheaton.edu/about-wheaton/statement-of-faith-and-educational-purpose/

Sadly, I can no longer find this illustration anywhere on the Internet.

Joy Clarkson (@joynessthebrave on Twitter/X/Elon Musk’s playground) has an excellent thread on this. You can find it here: https://x.com/joynessthebrave/status/1849544832693485885?s=51.

Joseph Ratzinger, The Nature and Mission of Theology, trans. by Adrian Walker (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 1995), 57.

Gaudium et Spes: Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, promulgated by Pope Paul VI on December 7, 1965, https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html.

Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred and Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder (London: Penguin Classics, 2000).

https://www.eldebate.com/religion/20211221/natalia-sanmartin-secularizacion-iglesia-quebrado-correa-transmision-fe-generaciones.html

https://www.plough.com/en/topics/culture/holidays/christmas-readings/mary-consoles-eve

https://www.baltimorecarmel.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Annunciation-Poem.pdf

Always good to read your writing again <3

Julia, I was so happy to receive a notification that you posted on ABIG! It was wonderful that the annual meeting was in San Diego this year and even better that you had a friend to accompany you. I’m looking forward to exploring the links you included. You’ve given me much to ponder. I definitely want to watch the movie Babette’s Feast as well as reread The awakening of Miss Prim. 😊